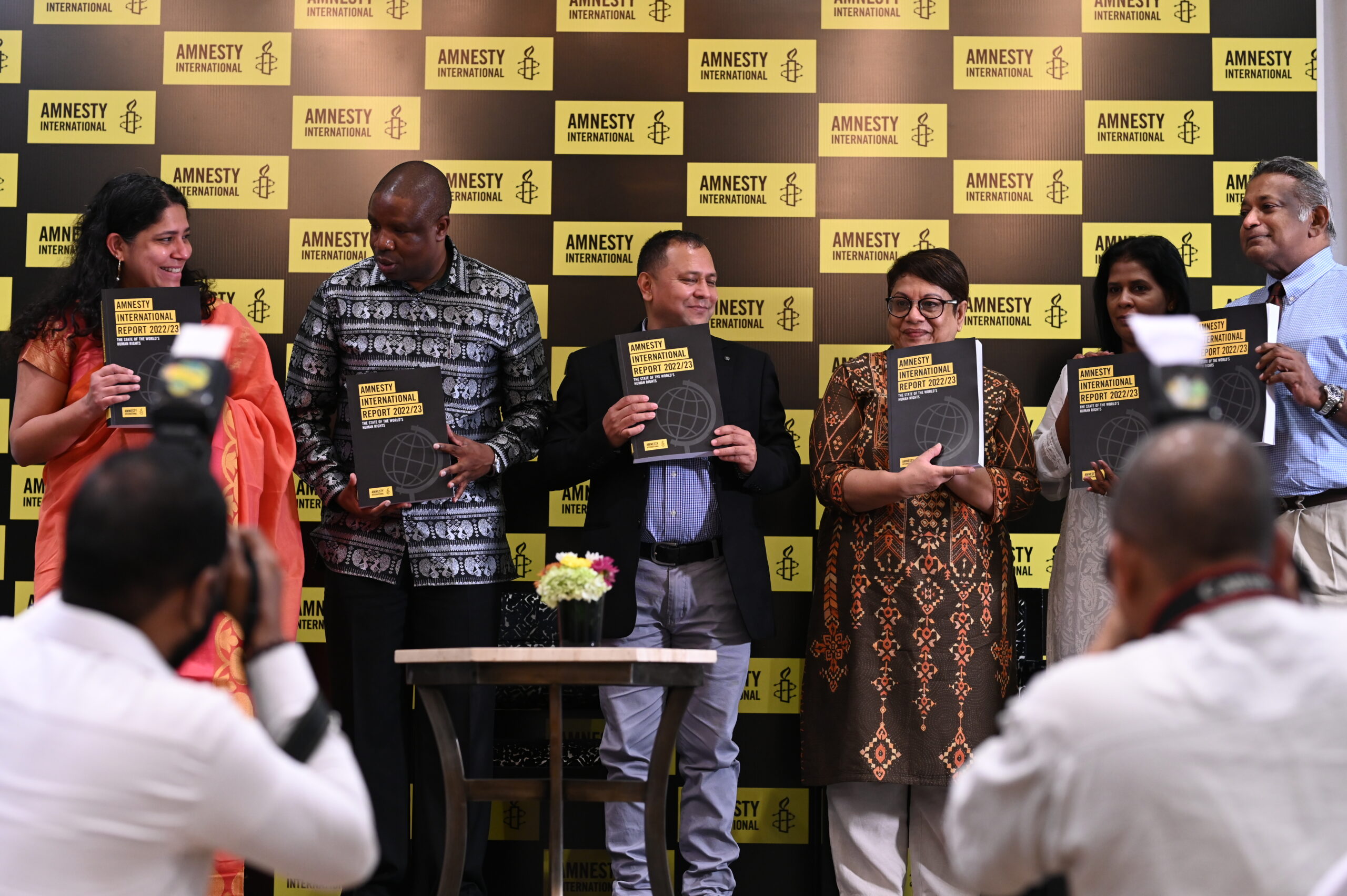

The failure of global and regional institutions – hamstrung by the self-interest of their members – to respond adequately to global conflicts, climate change and global energy and food crises has disrupted an already weak multilateral system, Amnesty International said as it launched its annual assessment of human rights around the world.

- Amnesty International’s Annual Report for 2022 highlights double standards throughout the world on human rights and the failure of the international community to unite around consistently applied human rights and universal values

- Robust response to Ukrainian crisis in the West is in sharp contrast with a deplorable lack of meaningful action on plummeting rights in Afghanistan and intense crackdown on the right to protest in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Maldives, India and Nepal

- Women’s rights and freedom to protest are threatened as states fail to protect and respect rights at home

- As the Universal Declaration of Human Rights turns 75, Amnesty International insists that a rules-based international system must be founded on human rights and applied to everyone, everywhere.

Amnesty International Report 2022/23: The State of the World’s Human Rights found that double standards on human rights abuses taking place around the world fuelled impunity and instability, including deplorable lack of meaningful action on the plummeting human rights record in Afghanistan, inadequate responses to a spiralling economic crisis in Sri Lanka and the refusal to confront the crackdown on dissent and persecution of minorities in multiple South Asian countries.

“The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created 75 years ago, recognizing the inalienable rights and fundamental freedoms of all people. Global economic dynamics and shifting power structures are unleashing chaos in which it is easy to lose sight of human rights. As South Asia sits on the brink of a volatile and unpredictable future, it is important now, more than ever, to keep rights squarely in the centre of all negotiations and conversations,” said Deprose Muchena, Senior Director at Amnesty International.

Ruthless repression of dissent

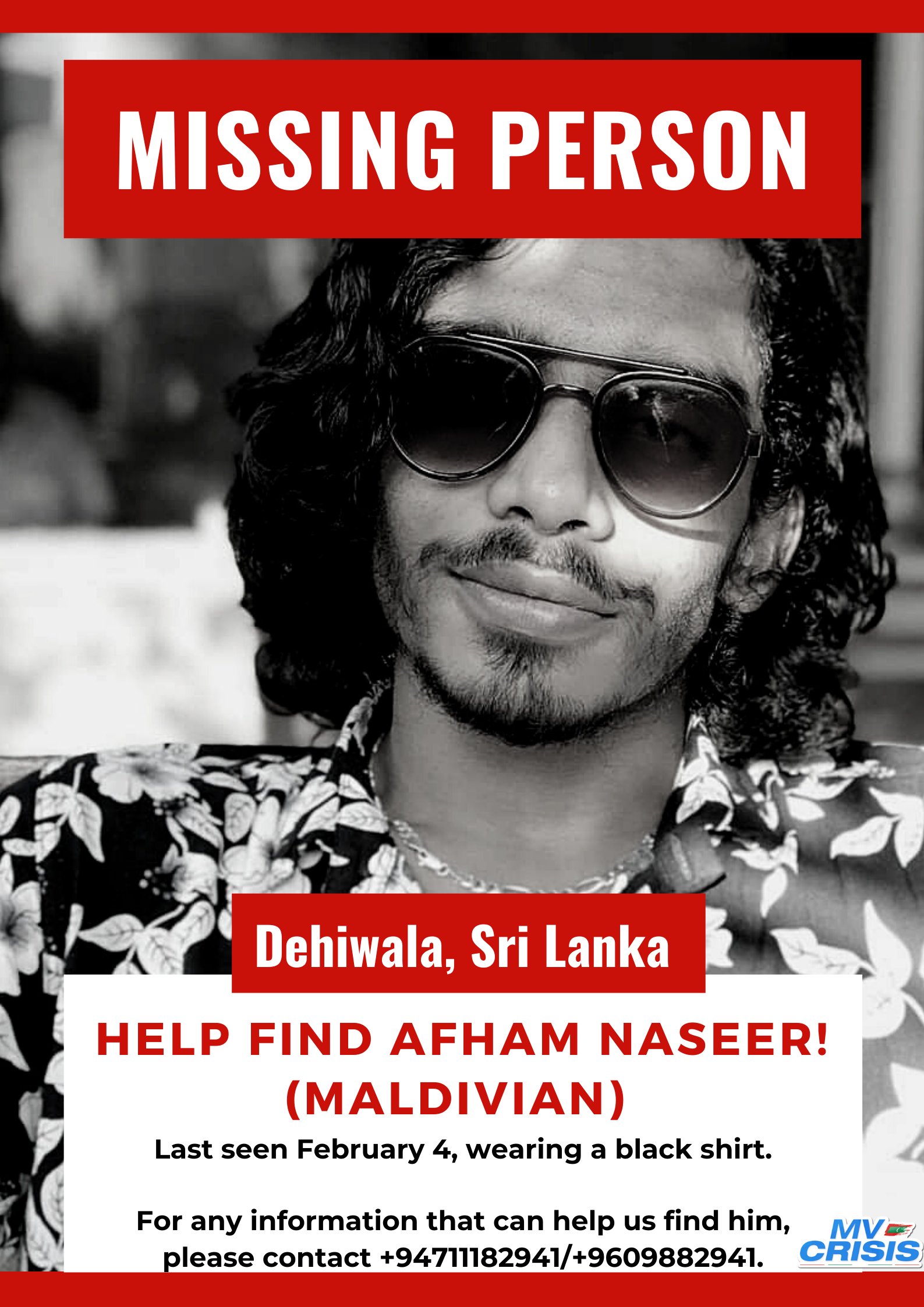

People took to the streets across the region to protest against injustice, deprivation and discrimination, but in most countries including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka they were met with intense crackdowns and excessive, sometimes lethal, force.

In Sri Lanka, emergency powers were used to curtail mass protests. The police used live ammunition, tear gas and water cannon against largely peaceful crowds protesting against the spiralling economic crisis, causing deaths and injuries. Protesters in Sri Lanka were arrested, arbitrarily detained and charged with terror-related and other offences.

In Afghanistan, peaceful protesters faced arbitrary arrests, torture and enforced disappearance. Police in Bangladesh used live and rubber bullets, sound grenades and tear gas to disperse protests by students and workers. In Pakistan, authorities forcibly broke up peaceful protests by activists and family members of victims of enforced disappearances. Protesting victims of loan sharks in Nepal were met with police baton charges and arbitrarily detained. In India, a 15-year-old boy and another protester were shot and killed by police during demonstrations in Jharkhand state.

Attacks on press freedom persisted in multiple countries. In Afghanistan, journalists faced arbitrary arrest and detention as well as torture and other ill-treatment for reporting that was critical of the Taliban. In Bangladesh, where journalists experienced physical assaults, judicial harassment and other reprisals for their reporting, a draft data protection law threatened to further curtail freedom of expression. Media workers in Pakistan also came under increased pressure as journalists and others were arrested on spurious charges.

The Indian government likewise tried to prevent the human rights situation there from being discussed abroad by imposing international travel bans on human rights defenders and detention without trial. It also used money laundering laws and other pretexts to harass media organizations and NGOs. In Nepal, comedians were among those who faced prison sentences in relation to their performances. The Maldives parliament passed a law that could force journalists to reveal their sources. Encouragingly, the Maldives government was considering amending the law, but faced strong criticism.

“South Asian countries seem to apply human rights law on a selective basis in a staggering show of blatant hypocrisy and double standards. They only criticize human rights violations when it aligns with their global and regional politics but are mute spectators to similar abuses at their own doorstep just because their interests are at stake. It is unconscionable and undermines the entire fabric of universal human rights,” said Yamini Mishra, Regional Director for South Asia at Amnesty International.

In response to growing threats to the right to protest, Amnesty International launched a global campaign in 2022 to confront states’ intensifying efforts to erode the fundamental right to freedom of peaceful assembly.

Women bear the brunt as states fail to protect and respect rights

In India the Supreme Court passed two progressive judgments upholding the right to dignity of sex workers and interpreting an existing law to expand abortion access to all women, notwithstanding their marital status.

Nevertheless, the reality for many women and girls in the region remained one of systemic discrimination.

In Afghanistan, women and girls were effectively erased from public life and spaces as new edicts further restricted their rights and freedoms which, in addition to banning them from working with NGOs, forbade them from travelling without a male chaperone, attending secondary school and university or going to public parks, among other restrictions.

In Nepal, women continued to be denied equal citizenship rights and, although the statute of limitations for rape was extended, the excessively short period for filing complaints remained a significant barrier to effective remedy for survivors.

Violence against women also remained prevalent in the region. There were calls on the Maldivian authorities by UN experts to address rising gender-based violence there. In Bangladesh, hundreds of incidents of rape or murder of women by their husbands or other family members were recorded and impunity for such crimes remained widespread. In Pakistan, several high-profile murders of women by their partners or family members were reported, yet the National Assembly failed to adopt legislation on domestic violence, pending since 2021. In India, violence against Dalit and Adivasi women, among other caste-based hate crimes, was committed with impunity. Girls were also banned from wearing the hijab in public schools in Karnataka.

“Women have been at the forefront of protests in the region, often challenging patriarchal control over their bodies, lives, choices and sexuality on behalf of the state, society and family. The failure of States and institutions to uphold gender justice leaves a terrible legacy of suppression, violence and stunted potential,” said Yamini Mishra.

Global action against threats to humanity woefully inadequate

Economic crises fuelled by pandemic-related recession, economic mismanagement and climate change induced disasters within and beyond the region severely affected economic and social rights, including in Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, where food, healthcare and an adequate standard of living became increasingly inaccessible.

In Afghanistan, the spiralling economic crisis plunged 97% of the population into poverty, while in Sri Lanka, inflation exceeded 73% in September 2022 with the poorest and most marginalized suffering the greatest consequences.

The devastating costs of the unchecked climate crisis were made abundantly clear in 2022. Specifically in Pakistan where heatwaves, droughts and then devastating floods had a catastrophic impact on lives and livelihoods of nearly 750,000 people. Against this backdrop, it was particularly disappointing to note that the global community failed to act in the best interests of humanity and address fossil fuel dependency, the main driver pushing us toward the biggest threat to life as we know it. This collective failure was another stark example of the weakness of current multilateral systems.

“South Asia is besieged by an onslaught of intersecting and interconnected crises including ‘man-made’ crises – with at least three countries in the region in the middle of an economic crisis and burdened with high debts – and natural crises, with South Asia often being ground zero for extreme heatwaves to destructive widespread floods. We stand no chance of surviving these crises if our national and international institutions aren’t fit for purpose,” said Yamini Mishra.

Dysfunctional international institutions need fixing

In Afghanistan, the space for independent human rights monitoring and reporting had all but disappeared. War crimes were also committed as the Taliban continued its campaign of reprisal killings against members of the former administration and security forces or those who oppose them. The Taliban’s version of a justice system lacked any credibility while the resumption of executions in Afghanistan represented a major regression. In India, authorities unlawfully demolished mainly Muslim-owned property in several states, raising concerns that this was a form of collective punishment for alleged involvement in intercommunal clashes. In Nepal, efforts toward securing truth, justice and reparation for crimes under international law and other human rights violations committed during the 1996-2006 conflict remained grossly inadequate.

Refugees and asylum seekers remained highly marginalized and at risk of refoulement. Ensuring the human rights of Rohingya refugees inside one of the world’s largest refugee camps continued to pose a major challenge for Bangladesh. While there was some improvement in access to education for Rohingya children, an estimated 100,000 remained out of school. Despite concerns from the international community and human rights groups, the Bangladeshi government persisted in its plans to relocate Rohingya refugees to the remote and flood-prone Bhasan Char island bringing the total number to 30,079 according to official figures.

Afghans fleeing persecution at home faced pushbacks from neighbouring countries, such as Iran, and other countries along the route, such as Turkey.

Impunity was compounded by the inability of the UN Human Rights Council to effectively address many of these serious concerns. It is vital that international institutions and systems that are meant to protect our rights are strengthened rather than undermined.

Amnesty International is also calling for the UN’s key decision-making body, the Security Council, to be reformed to give a voice to countries and situations which have been traditionally ignored, especially in the global south.

Shameless double standards pave way for further abuse

The Russia-Ukraine war diverted resources and attention away from the climate crisis, other long-standing conflicts and human suffering the world over and in South Asia in particular. The West’s double standards only embolden and enable countries to evade, ignore and deflect criticism of their human rights record.

“There is no denying that an effective and consistently applied rules-based international order is the need of the hour. The Russian war of aggression in Ukraine demonstrated that some of the richest countries in the world were more than capable of receiving large numbers of people seeking safety and giving them access to health, education and accommodation. However, the West did not offer the same treatment to the Afghans and Rohingyas escaping war and repression. This shameless double standard must be challenged and countries must step up their efforts for a renewed rules-based order,” said Deprose Muchena.

“The double standards of wealthy nations are as evident in their sickening COVID -19 vaccine nationalism as it is in their large contribution to climate change. As South Asia increasingly becomes ground zero for many climate emergencies, it further highlights the need for reparations for loss and damage in these nations with greater investment in global reduction in dependency on fossil fuels. We also need countries, including in South Asia, that have so far failed to take a stand against human rights abuses in the world to speak up now before it is too late for everyone, everywhere.”